Keyshawn Johnson’s book about breaking the color line in pro football is a must-read for all Americans, not just football fans.

The Forgotten First, a new book by Keyshawn Johnson and Bob Glauber, is a must-read not only for Cleveland Browns fans, not only for football fans, but for all Americans as it tells how professional football became racially integrated a year before Jackie Robinson broke the color line for Major League Baseball with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Yet although almost everyone knows the story of Jackie Robinson, for a variety of reasons it has been almost forgotten that professional football became integrated first.

Cleveland fans, did you know that Hall of Famers Marion Motley and Bill Willis were the two African American players who debuted in 1946 for the Browns in the new All-American Football Conference? At the same time, the older National Football League featured Kenny Washington and Woody Strode, two UCLA alumni teammates of Jackie Robinson (yep, that Jackie Robinson who broke the color line in baseball for the Brooklyn Dodgers).

Washington and Strode played for the 1946 Los Angeles Rams who had won the NFL Championship the previous season as the Cleveland Rams in 1945. Those four African American players broke the color line for professional football permanently, after earlier attempts had failed.

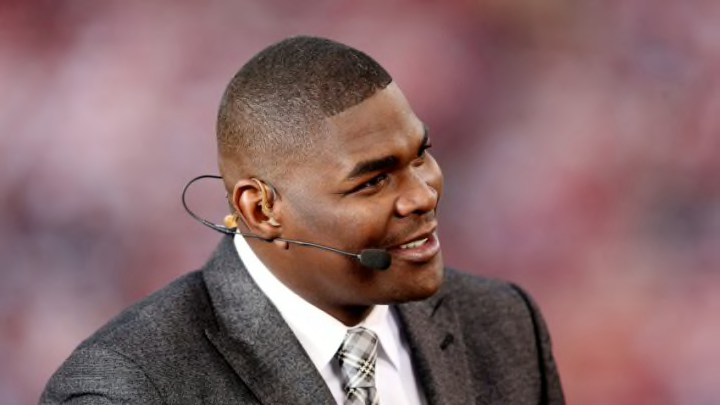

Johnson is a great storyteller with media clout, street cred, and player credentials that include a Super Bowl ring as well as being a former first overall draft pick in the NFL, three Pro Bowl berths, and over 10,000 receiving yards. Glauber is a premier sports journalist and former president of the Pro Football Writers Association and a two-time winner of the New York State Sportswriter of the Year.

Together, they are able to keep the story exciting and moving, while also absolutely factual and on track. It’s a perfectly entertaining book from a pure football perspective but it’s also an important social commentary that has significant historical value. Like many wide receivers, Johnson has the reputation of being very spontaneous and a little wild, although people tend to underestimate him. Glauber provides the seriousness and scholarship to offset Johnson’s more colorful public persona.

Their book should be mandatory reading for all rookies as soon as they are drafted or sign free-agent contracts. They need to know where they come from and as well as something about the various stops along the way, including the bumps in the road.

In Cleveland’s case, the stars of the story were Motley and Willis, as well as coach Paul Brown. But the white players, notable men like Groza and Graham, stepped up for them also.

Some other tidbits that are dropped include the revelation that one lineman from the Los Angeles Dons in 1946 used razor blades hidden in his hand wrappings, and jammed them into Willis’ body when he got the chance. Willis didn’t react, other than to outplay his rivals.

Later, in Miami, there were death threats against both Willis and Motley. Paul Brown handled it by paying Willis and Motley to stay home when the team traveled to Miami without explaining why until years later. This kind of behavior — on both sides — seems unbelievable by today’s standards. But it wasn’t 2021, it was 1946, and people did what they felt they had to do.

Can you imagine someone feeling that it was a good idea to jam a razor blade into the body of another human being in a sporting event, just because that person was of a different race? What could make a person so twisted? And on the other hand, how could a person tolerate that kind of abuse without flinching? Amazing.

Page two of this article reviews Johnson and Glauber’s account of the ban on African Americans from 1934-1945, and the leading role of the Washington franchise.